|

του Γιάννου Δημητρίου

Είναι με μεγάλη χαρά και περηφάνια που πληροφορηθήκαμε ότι ο συγχωριανός μας, Γεώργιος Μίας, Επίκουρος Καθηγητής του Πολιτειακού Πανεπιστημίου του Μίσιγκαν (MSU) των Ηνωμένων Πολιτειών ανήκει στην μικρή ομάδα εξαίρετων επιστημόνων ερευνητών που θα μελετήσει τις επιπτώσεις στην υγεία των αστροναυτών που αναλαμβάνουν διαστημικές αποστολές μακράς διαρκείας. Είναι με μεγάλη χαρά και περηφάνια που πληροφορηθήκαμε ότι ο συγχωριανός μας, Γεώργιος Μίας, Επίκουρος Καθηγητής του Πολιτειακού Πανεπιστημίου του Μίσιγκαν (MSU) των Ηνωμένων Πολιτειών ανήκει στην μικρή ομάδα εξαίρετων επιστημόνων ερευνητών που θα μελετήσει τις επιπτώσεις στην υγεία των αστροναυτών που αναλαμβάνουν διαστημικές αποστολές μακράς διαρκείας.

Έχουμε εντοπίσει δημοσίευμα στην εφημερίδα Detroit Free Press, ημερομηνίας 28 Δεκεμβρίου 2018, όπου αναφέρεται στην μεγάλη επιτυχία του να εξασφαλίσει χορηγία από την NASA για την διεξαγωγή σχετικής έρευνας.

Ο Γεώργιος Μίας είναι επίκουρος καθηγητής Βιοχημίας & Μοριακής Βιολογίας στο MSU, και ένας από τους 15 επιστήμονες σε όλη την Αμερική που πήρε διετή χορηγία από το Transnational Research Institute for Space Health (TRISH) του Baylor College of Medicine για τη διεξαγωγή της σχετικής έρευνας. Το πρόγραμμα είναι χρηματοδοτημένο από τη NASA και ξεκίνησε το 2006 με στόχο «να προβλέψει, να προστατεύσει, να διατηρήσει την φυσική και πνευματική υγεία των αστροναυτών κατά τη διάρκεια διαστημικών αποστολών μακράς διαρκείας».

Πιο κάτω παρουσιάζουμε αυτούσιο το άρθρο στην αγγλική γλώσσα.

Astronauts on Mars? MSU professor helps NASA plan to keep them healthy

Keith Matheny Detroit Free Press

Published 9:13 AM EST Dec 28, 2018

NASA's lofty future plans include a return of astronauts to the moon, building bases there to foster deeper space missions, and manned missions to Mars possibly as soon as the 2030s.

Getting there will take overcoming not only massive financial and technological hurdles, but biological ones as well. How can astronauts stay healthy on a Mars mission that might be a three-year round trip, especially with no hospital or even real-time communications with Earth should something go wrong?

A Michigan State University professor has received a two-year research grant to join other experts across the country, putting their collective brain power together on issues related to astronauts' health on long-term space missions.

George Mias, an assistant professor of biochemistry and molecular biology at MSU, is one of 15 scientists nationwide to receive two years of research funding from the Translational Research Institute for Space Health (TRISH) at the Baylor College of Medicine. The NASA-funded program started at the Texas school in 2016 "to predict, protect, and preserve astronaut physical and mental wellness during deep space exploration missions."

Mias' focus will be precision medicine, an emerging field using multiple technologies to detect changes in an individual's wellness; diagnose it, treat it, and possibly prevent diseases. The goal: an integrated, precision health profile for each astronaut on a long-term mission, continuously analyzing thousands of bodily actions, conditions and functions - even down to the molecular level - and seeing how they change over time.

"Our hope is to characterize an individual wellness baseline for each astronaut in a healthy condition, and classify departures from this baseline wellness," he said. "We want to be able to provide timely alerts to deviations from health, identify the medical condition causing them, so that we can have early interventions as necessary."

More:

Former U.P. resident helps detect colliding black holes in space

Michigan meteor is the gift that keeps on giving for scientists

NASA joins fight against invasive Great Lakes shoreline plant

The human health challenges from the kinds of deep-space missions being envisioned are "a complete departure from what we have currently with low-Earth orbit and our experience with the moon," said Emmanuel Urquieta, senior research portfolio manager for the TRISH program at Baylor.

The main concern is the radiation exposure to which astronauts would be subjected, he said. According to NASA, space radiation beyond low-Earth orbit may place astronauts at significant risk for radiation sickness, and increased lifetime risk for cancer, central nervous system effects, and degenerative diseases.

A round-trip mission to Mars might take three years in total, Urquieta said.

"There's not going to be any ability to resupply the mission with new medications, new food," he said. "Then there are the psychological effects from isolation and confinement. This is going to be a crew of about four members working in very close proximity for the entirety of the mission."

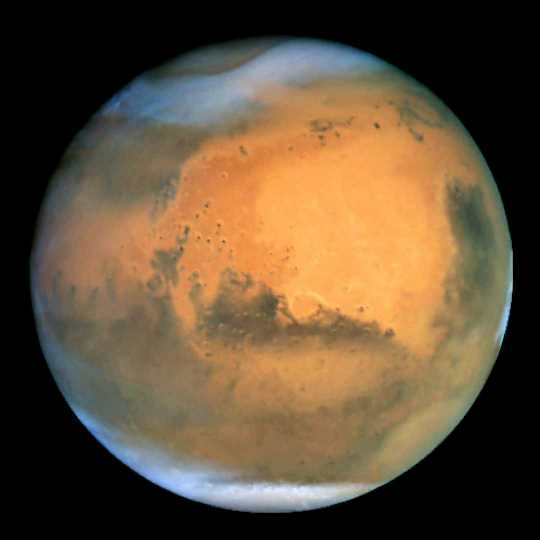

In an image that scientists call the sharpest image ever made from Earth, the planet Mars is seen as a dynamic planet covered by frosty white water ice clouds and swirling orange dust storms above a vivid rusty landscape, in this view made by the Earth-orbiting Hubble Space Telescope on June 26, 2001.

NASA and Hubble Heritage Team/AP

On space shuttle orbits or the Apollo moon missions of the late 1960s and early 1970s, the time delay for communications between the astronauts and Mission Control in Houston was seconds at most. But the radio delay from a Mars mission could be more than 20 minutes, because of the sheer distance - 34 million miles - that the radio signal has to travel back to Earth.

"So most of the medical decision-making in a crisis situation is going to have to be made by the astronauts themselves, in the moment," Urquieta said.

Michigan astronaut's experience

Jack Lousma was one of NASA's early test subjects on studying the health effects of longer periods in space.

Lousma, who was born in Grand Rapids and grew up near Ann Arbor, piloted Skylab-3, a nearly two-month mission aboard NASA's first orbiting space station, from July 28 to Sept. 25, 1973. He later commanded the third-ever space shuttle flight, aboard Columbia on an eight-day orbital mission in March 1982. Lousma also supported three Apollo moon missions from Mission Control in Houston, including Apollo 13, immortalized by Hollywood. After an explosion on their way to the moon, when astronaut Jack Swigert actually uttered, "Houston, we've had a problem here," it was Lousma receiving that message.

No astronaut had spent more than two weeks in zero gravity up until Lousma and Skylab-3 crew's nearly two months in space.

"No one knew what was going to happen to you," said Lousma, now 82, who left Michigan in 2014 and now lives in Kerrville, Texas, close to family.

"We came back to discover we had 20 percent less blood, 10 percent fewer red blood cells and were not making anymore. At that time we had immeasurable bone loss, because we didn't have the equipment to measure that small of bone loss."

Curiously, on the next Skylab mission, where astronauts spent three months aboard, red blood cell production resumed, Lousma said.

"It seems the body stabilizes at some level that it feels it needs at that particular condition," he said.

The Skylab flights were precursor to much longer deployments on the International Space Station, up to nearly a year. NASA has learned astronauts on such long missions experience 1- to 2-percent bone loss per month, Lousma said.

"Your bones don't have any load on them, so they tend to deteriorate," he said. "That's why they've implemented exercise equipment to help prevent that from happening. Some things we recognized early have been mitigated in one way or another."

Astronauts have also experienced vision problems in space, Lousma said, likely because of differences in how blood is distributed in the body and zero gravity putting pressure on the back of the eye.

A mission to Mars would take such issues to a whole other level, he said.

"The major problem has to do with radiation," he said. "That's something they've got to work on; they haven't solved that problem yet.

"You're several months away from any kind of medical attention. You're going to have to mitigate those kinds of problems through training and the ability to do medical solutions onboard."

Mental and emotional health is just as important, Lousma said.

"It's not going to do to look out the window for eight months on the way to Mars, and eight months on the way back," he said.

Mars has only about 38 percent of the gravity of Earth. But after more than half a year of weightlessness, it would leave astronauts feeling as if they couldn't lift their foot off the ground.

"They'll need a one-person centrifuge every day, to put the loads on the bones," Lousma said. "When you arrive at Mars, you want to be ready to go when you get there, to get some work done - not sit for a week in quarantine."

What to eat and drink is another major obstacle, Lousma said.

"There are no grocery stores out there, and you can't bring along enough food for three years," he said.

Lousma said he supports the approach of first returning to the moon, building a presence there, and then going out on deeper space missions from there, in advance of a manned Mars mission attempt.

"See if we can't find out whatever other problems might be out there being in space for a year or more," he said.

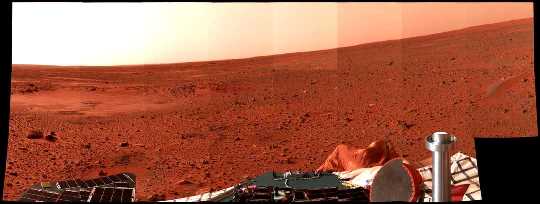

In January 2003, a Mars landscape is seen in a picture taken by the panoramic camera on the Mars Exploration Rover Spirit. The circular topographic feature, dubbed Sleepy Hollow, can be seen along with dark markings that could have bee caused by the airbag-encased lander as it bounced and rolled to rest.

NASA/Jet Propulsion Laboratory/Cornell University via Getty Images

The space program has long had its critics, questioning the huge costs while other societal needs persist at home. Lousma said it's still worth it, and pointed to NASA-driven technological improvements now benefiting everyone, in everything from LED lighting to computers to cordless vacuums.

"When Columbus came here, the King and Queen of Spain were dealing with slums, a lack of health care, a need for better housing," he said. "If you go to Spain today, is that cleared up? No. These kinds of problems never get solved. Why not go on and see if you can learn something new and different, that might make those problems go away?"

'We are making history here'

Mias said he looks forward to getting to work on the research.

"We are really excited to receive funding from TRISH and become members of this great family of researchers," he said.

Urquieta called the work an honor.

"I feel very proud to be able to work for TRISH, to be a part of this," he said. "We are really making history here. And once we go to Mars, I want to be able to tell my kids that I helped a little bit ? just a drop of water in that big, big mission."

Σημείωση: Ο καθηγητής Γεώργιος Μίας είναι υιός του Ιωάννη και της Χρυστάλας Μία. Ο κ. Ιωάννης Μίας διατέλεσε μέλος της Επιτροπής του Πολιτιστικού Συνδέσμου "Η Άσσια" για πάρα πολλά χρονιά και υπηρέτησε ανιδιοτελώς τον Σύνδεσμο μας από την θέση του Μέλους, του Ταμία και του Αντιπροέδρου. Ο κ. Ιωάννης Μίας κατά τη διάρκεια της προσφοράς του στον Σύνδεσμο μας επιμελήθηκε την εξαιρετικής σημασίας και σπουδαιότητας έκδοση του Πολιτιστικού, "Ιστορικό του χωρίου Άσσια - Μαρτυρία Γεώργιου Π. Πάκκου".

|